The Original CS1 Camshaft Engine

Norton’s first OHC engine was the CS1 (Camshaft Engine 1 –

yes, I know, not very imaginative) and was designed by Walter Moore

over the winter/spring of 1926-27. It was of a completely different

design format to the engine that later became the Manx, but never the

less used the bore and stroke dimensions of 79x100mm that had become

synonymous with Norton 490cc single engines of the time. It was also

the real start of Norton’s racing story so holds a very important

place as being the first in a long lineage of camshaft single cylinder

engines.

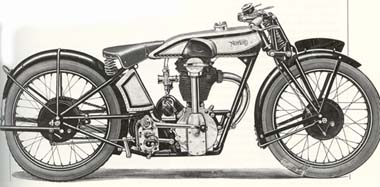

This first engine had a very distinctive timing case and bevel tube,

giving it a very pretty ‘cricket bat’ look when viewed from

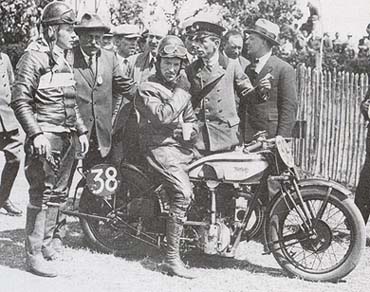

the timing side. Although very successful at its first introduction

(in the hands of Alec Bennett it won the 1927 Senior TT, with Stanley

Woods, similarly mounted, setting fastest lap at 70.99mph before retiring),

it was not actually very reliable, and many engine failures occurred

alongside the successes. Stanley Woods later commented that he remembered

when Walter Moore was designing the engine, he had both a Chater Lea

and Velocette in his office, and thought he had probably taken the worst

features from both bikes.

1929 went just as badly with reliability and overheating problems being experienced and no good results other than a single GP win in Spain 1929. Walter Moore was rapidly loosing the confidence of his employers, and this added to the fact that Joe Craig had taken over the race team and was not a supporter of Moore, meant his days were numbered.

In 1930 Walter Moore had one disagreement too many with the Norton management of the time and decided to leave to go to NSU, where he had been offered a very good position. He there designed a very similar engine for them, which stayed in use for many years. A wit of the time commented that the initials might have stood for ‘Norton Spares Used’!

It was Arthur Carroll that was given the task of designing Norton’s second OHC engine (with much input from Joe Craig, who became legendary in his own right as Norton’s racing team boss and engine guru), and it was this masterpiece of motorcycle engineering, that went on to become probably the most famous and successful racing motorcycle engine of all time. Comparable maybe to the Ford Cosworth DFV engine in the car world – as an engine/bike that could be bought ‘off the shelf’ by any customer and be immediately competitive in international class races.

A little known fact was, that Carroll’s first version of this engine was in fact a hybrid, sharing a Walter Moore top half in conjunction with his newly designed bottom half. This bike was shown at the 1929 Olympia show in November, although it seems unclear if any were ever sold to customers.

The full Carroll engine’s first outing was in the North West 200 in Northern Ireland in April 1930 where in 350 guise it got its first win. However, 1930 was the year of Rudges in racing and there was to be no fairy tale first TT outing that year, with the Rudges taking 1,2,3 in the Senior and 1,2 in the Junior with the 350 Norton again getting the best placing of 3rd place. However, the good news was that the engine was proving to be reliable (unlike the earlier CS1) and later in the year extra horsepower was found with the result that Stanley Woods was able to take the 500 to a win in the wet at the Ulster, with Jimmy Simpson quickly following this up with a Grand Prix win in Sweden.

The new model was offered to the public late in 1930 (although still being advertised as the earlier CS1 and CJ model types) and also boasted a modified and updated chassis. Given that at this time the Wall Street Crash had really began to have an effect the world over and with many other motorcycle companies going to the wall, Norton’s good fortune in surviving must undoubtedly be owed partly to the success of this new model.

The earliest of the Carroll engines had a slightly different cylinder

stud spacing to later engines, and did not have an oil pressure indicator

or oil filter in the crankcase timing case. Also apparent in the earliest

photos of the racing model in 1930 was an additional oil pipe running

from the right side of the front cambox, down to the corresponding area

of the timing case. I assume this was to assist oil drainage, although

it was removed by the time the 1931 model range was introduced. This

earliest of models also looked to have a top bevel inspection cover

with a slightly different curve to later models.

Another interesting point with the early versions of the engine is that

they were fitted with standard coil valve springs. This is surprising

really, when one of the International and Manx engines most well known

and refining features was its later use of exposed hairpin valve springs,

with associated oil loss! Hairpin springs were not introduced until

1934.

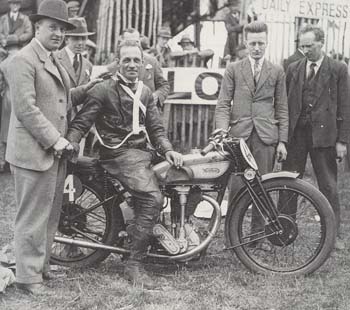

1931 was really where it all started to take off for Norton where racing was concerned, with many wins throughout the year, including a reversal of fortunes in the coveted TT, with Norton now taking the first 5 places in Junior and Senior events. The first of many multiple TT wins over the next few years and the start of what was probably Norton’s most successful period. From this point forward until the end of the 1930’s they dominated international events with wins in both classes throughout the decade.

Incidentally, a testing session on Pendine Sands with Joe Craig and Tim Hunt in March 1931 gave a best speed on the 500 of 118mph, which was no mean at all for a bike intended for road racing, not out and out speed attempts.

1932 saw the first serious attempts by Norton at weight loss for their works bikes. Many items were produced using light alloy, but what was particularly interesting, is that this was the first time that a magnesium based alloy was used, being employed for the crankcases. The magnesium alloy used by Norton’s was called Elektron and was typified by a blackish finish, as a result of the chromate finish used to protect the bare metal from the elements (all magnesium alloys corrode badly when exposed to the atmosphere).

As a footnote to this, I have to say that when writing this article even I was surprised to find that Elektron was employed as far back as this (I would have said 33-34), but even more surprising was that supposedly the gearbox shell was also cast in the same material. I have only ever seen one genuine pre-war Norton using a magnesium gearbox shell and this is Ian Bain’s very successful VMCC winner, which I gather is a genuine 1935 Works bike, Jimmy Guthrie’s if I remember correctly. Talking to Ian’s father last year, I gather this shell has now got very brittle and has cracked numerous times. I believe it is now at a point where it is not useable for serious racing and needs to be replaced.

I know that a company also made larger capacity magnesium gearbox shell’s post-war, specifically for the Norton upright gearbox’s that were employed in Cooper Cars. I have seen one of these shell’s and the sump is enlarged in the area forward of the gear cluster. I was told that the company that made these shells also made the magnesium shells pre-war for Norton, but cannot confirm this.

Anyway, back to 1932. As well

as the alloy bits and a larger fuel tank, another key change was the

introduction of checksprings on the girder forks, which according to

Stanley Woods made a big difference. Racing machines were fitted with

a wider spring than their road going counterparts and were parallel,

not tapered.

If there was a point where it could be argued that the road going version

and the out and out racing bikes first started to go their separate

ways, then in many respects it was at this time, and was the beginning

of what later became the Manx racing version.

As an example of this (and one that even I had not noticed until a couple of years ago), the parallel springs employed on racing Norton’s were not the only difference on the front forks. Look closely on genuine racing Norton’s fitted with girders from this point forward and you will note that they were not fitted with a side damper on the lower spindle, as all other Norton’s were (including the International and CS1). I assume this was because the better handling associated with a parallel spring precluded the need for a damper and in most cases the racing machines were also fitted with a top mounted Andre damper. Although of marginal benefit, I expect the lack of this extra metal meant slightly less un-sprung weight as well (not sure if the benefits were understood at the time though!). If you look at the photographs of my own 1938 rigid racer on the homepage you will note it is fitted with these parallel springs and no side damper.