| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Building

the Engine - Part 1: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Last

Updated : 07/05/10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Whats the Current Norton

Project?

Well, I havent really had much chance to work on my own bikes

much in the last few months, work, mail order and visiting friends

with illness have taking precedence. That said, since Xmas 2009

I have been very slowly building a 1937 International engine

which I am going to be using as a test bed ('Works Hack' I kid

myself) for testing new parts, in a rigid Inter roadgoing bike.

Anyway, I had a few days holiday this week, so have managed

to do a bit of work on it and having already done the prep work

on the main castings, I have now started the rebuild. I had

already checked and re-balanced the crank, cleaned up and blasted

the crankcase castings, so this week I have taken out the oil

pump and given it the once over, and have just finished fitting

the new main bearings.

For the engine rebuild, I thought it would be nice to treat

myself and spend a morning going through my own stock, to sort

out everything I needed - something I very rarely do, but I

had to remind myself - this was the main reason I originally

setup the spares manufacture - so I would have parts for my

own bikes! Anyway, I spent a couple of hours going through all

my stock and taking one (or two!) of everything - a bit like

Xmas! So the engine will be pretty much fully fresh on the inside

and have my full collection of parts in it: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Preperation Work |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inter in a Box!

Inter in a Box!

1937 International engine as it arrived from Aussie

|

|

|

The basis for the engine

was a very straight and original 1937 International engine that

had come from my good friend Arthur Moore in Australia. As always,

Arthur had done a wonderful job of packing all the parts up safely

and had even included a little bit of Australian written culture

for me to read when I opened up the package - thanks for that

Arthur!

As with all Arthurs parts, the engine was lovely and unmolested

and exactly as he had described it - very much like it used to

be if finding an original engine at an autojumble 30 years ago.

Unfortunately nowdays, if an engine ever does come up for sale,

it is far more probable it will have been put together in the

last 6 months with a collection of non-matching dross.

I don't mean to get all weepy eyed and nostalgic, but when buying

parts from Arthur it reminds me what it used to be like when parts

were more plentiful here in England, and you could find engines

where there was a possibility you were the first person to have

looked inside it in the last 40 years, Ahh - them were the days

. . . |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Having unpacked the engine - which

was basically a complete bottom end and barrel + a spare barrel

that needed relinering, I carefully stripped it down and inspected

it. I found everything pretty much as I hoped to find it. the

crankcases were in excellent overall condition and I was very

pleased to find that the inner timing case, which is of the

'breathered' variety fitted in the late 1930's, shared the same

number as the crankcases - just confirming what I said earlier,

that this was an unmolested engine, with matching original parts.

Note: In reference to the inner timing case breathing - there

were two variations. Standard 1930's engines have a hole in

them, above the oil pump drive bearing, that allows the timing

case to 'breathe'. This hole corresponds to a milled away area

of the timing case chamber on the timing side crankcase. Later

International engines, and magnesium timing covers did not have

these holes, as the crankcase timing chamber had a breather

union exiting out of the top |

|

Crankcases, with

everything stripped, just before blasting.

Crankcases, with

everything stripped, just before blasting.

Notice breather hole in timing case, above lower

screw hole

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inside of crankcases,

showing the original bearing retainer plates,

which I later removed to check the bearings. Bottom

bevel housing and gear also visible

Inside of crankcases,

showing the original bearing retainer plates,

which I later removed to check the bearings. Bottom

bevel housing and gear also visible

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The drive side crankcase

had a small piece broken off it at the rear, on one of the engine

bolt surrounds - a very common problem and not serious at all.

I could have got away with leaving this, but I do not like anything

like this on an engine I am rebuilding (it would play on me

every time I looked at it!), so that and a small cosmetic 'knock'

on the timing case were set out for alloy welding. I did initially

attempt to carry out this welding myself - using my newish DHC

2000 oxy-acetylene torch, which supposedly makes alloy welding

a doddle. Although I had had some success with this new torch

(which has much greater heat control than the standard oxy-acetylene

torch I have been using for 20 years), I was not successful

with the crankcase and eventually had to concede defeat and

send the crankcase off to my normal welder in Leicester - Arthur

Sosbe.

Once the crankcase was back and cleaned up, I gave them and

the timing case a light blasting - having first carefully masked

up every orifice. Even so, the light blasting grit gets everywhere,

and when removing all the blocking material I had to very carefully

wash every oilway and cavity to ensure every spot of grit had

been removed.

My original intention was to get this engine\bike up and running

as quickly as possible. Although I want it to be mechanically

good - I do not want it to be too pristine because its main

purpose is to be a 'Works Hack' that can be used to quickly

test out any new parts on the road. I have mentioned this to

my best mate Andy Phillips and suggested he might like to be

a 'test rider' - where I give him the bike for a few days and

ask him to go and put a few hundred miles on it!

Anyway, as part of this - 'get it together quick' philosophy,

I was hoping I might get away with keeping the original Bigend

and Mains bearings in for the moment. On inspection, the Bigend

felt good and the crank very true, so that is worth keeping

for the moment.

However, although the mains initially felt fine, having gently

heated the crankcases up, so I could unsolder the bearing cover

plates to inspect the bearings - the timing case bearing virtually

dropped out, showing signs it had just started spinning in the

crankcase - not brilliant, but not uncommon at all. I carefully

inspected the crankcase bearing surround - to see how serious

the spinning of the bearing had become. There was just a slight

matt greyness, but no bad scoring, indicating that the bearing

had only just started to spin when hot - and therefore did not

yet warrant the serious remedial surgery of machining the crankcase

bearing area to take a sleeve - which is not something you want

to do unless you really need to. When there are signs that the

bearing is starting to slip though - it really needs to be replaced,

to ensure the best chance of full interference tolerence is

maintained, with new bearing.

Moving on to the drive side bearings, on heating up the crankcases

to remove the bearing retaining plate I found the bearings on

that side also came out quite easily, but on close inspection

of the roller bearing I found two things:

1. the bearings was not a lipped roller - not strictly necessary

if the spacer is correct - but it always should be!

2. the outer cage had corrosion on the bottom, where all the

weight had been sat over the years. This effectively made the

decision for me, yes the bearings will definitely all need to

be changed. (see further down)

Anyway, that made life much simpler, because it meant that I

did not have to worry about washing bearings out etc. I had

already committed to lightly blasting the cases externally,

and had carefully taped every orifice up with double layers

of Gaffa tape, but once I had made this decision to change bearings,

it removed any doubt about if this taping up had been unsuccessful

and eradicated the need to carefully rinse and degrease them

afterwards. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Very nice, straight

Inter crank, after a few hours cleaning it up.

It showed as running true as well

Very nice, straight

Inter crank, after a few hours cleaning it up.

It showed as running true as well

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The original

driveside roller bearing showed a definite

track mark, and the case hardening destroyed

in one spot - these would make a hell of a

noise if not replaced and would soon fail

completely. Note that this bearing is not

the lipped variety either - which it should

be

The original

driveside roller bearing showed a definite

track mark, and the case hardening destroyed

in one spot - these would make a hell of a

noise if not replaced and would soon fail

completely. Note that this bearing is not

the lipped variety either - which it should

be

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cylinder Head and Barrel |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nice condition

standard International cast iron barrel.

This is after honing and has just been blasted

and high temp painted

Nice condition

standard International cast iron barrel.

This is after honing and has just been blasted

and high temp painted

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The barrel was nice and easy. As part

of the deal, Arthur had found two nice straight standard Inter

cast iron barrels. Both had all fins on them (an amazing rarity

in itself!), one was a good standardish size, just needing a rebore,

the other had been bored out until it had gone through the side

wall - which meant it would need re-linering, but this second

one was just a sweetener for the deal and would provide a good

basis for a future restoration.

For this build the first barrel was perfect, so all I needed to

do was give it a blast and then send it to my local car factor

motor engineers for a rebore, where it was ready for collection

within two days - job done!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Delapena

Honing machine now installed in my workshop

- which means I can hone bigend eyes after

pressing them into conrod

Delapena

Honing machine now installed in my workshop

- which means I can hone bigend eyes after

pressing them into conrod

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Incidentally, this visit

to my local auto engineers turned out to be very fortuitous for

another reason. They are a sikh family who have been refurbishing

car and lorry engines since the late 1960's. I can remember visiting

them in the late 1970's when I first started restoring bikes.

At one time they employed about 25 people and refurbished hundreds

of engines per month for fleets etc. Well now the original father

is close to retiring and his lads have other interests as well

as the automotive side, so the auto engineering business is much

smaller. I mentioned to him that I had been looking for a Delapena

honing machine for some time, for honing Bigends. With a wry smile

he told me to come round the counter and follow him to the workshops.

In a far corner, next to a huge and very expensive vertical borer\honer,

was a Delapena Auto Speedhone looking clean, but like it had not

been used for some time! It transpired it had gone out of use

about 10 years ago when they got the new machine, but that it

had had a very expensive service and bearings replaced just before

it was decommisioned (he reckons the service had cost well over

a £1000). He knew how good the machine was, so he was not

going to let it go cheap - but the clincher for me was looking

through the tooling that came with it and finding the correct

honing bar for Norton bigends in very good condition, plus a brand

new 'sizing ring' for same. These two alone to buy seperately

I had already found out would cost me approx £350 + VAT.

Needless to say, it was not long before a deal was done and the

honing machine was stripped down to a point where Andy and I stood

a chance of trollying it into the back of my van. Another little

bonus on stripping it was finding that it had a tank full of Delapena

honing fluid that I was told was brand new when they put the machine

out of service - approx 50 litres, or £120 quids worth.

Wahhay.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tank

and filter system under Delapena is

quite elaborate and holds approx 50

litres of honing fluid

Tank

and filter system under Delapena is

quite elaborate and holds approx 50

litres of honing fluid

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

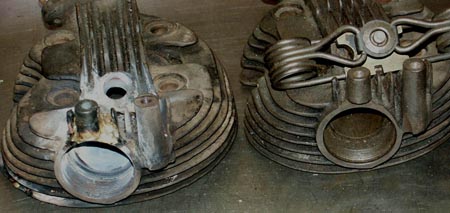

Cylinder Head Removation

As I had already mentioned, the bottom half had come from Australia

complete, but that meant the head and cambox needed to come from

elsewhere. Well luckily I already had a couple of standard iron

heads 'on the shelf', but the better one of the pair was really

part of a spare Inter engine which I wanted to keep together,

as it was all nice and orginal, with all the main castings in

good condition. This I had always considered my 'spare' engine

for the Racing Inter.

My other 500 spare head was in nowhere near as good a condition,

and I had always considered it as a 'last ditch' spare when I

had nothing else left. It had 3 key faults -

1. It had two broken fins surrounding the bevel tube cutaway (not

in itself serious)

2. It had the front head steady mount over the exhaust port broken

away (serious)

3. A common problem with iron heads - a crack from the spark plug

to exhaust valve seat (serious)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

If

you look carefully you can just make

out a hairline crack running from

the exhaust port to the valve seat

If

you look carefully you can just make

out a hairline crack running from

the exhaust port to the valve seat

|

|

After some thought, I

figured that a little bit of extra work now, might result in turning

a sows ear into a silk purse, and mean I dont have to use up the

decent head - so I decided it was worth giving this head a go.

To address the simple problem first, I cut up a couple of steel

plates to roughly the same shape as the broken fins. I then put

these to one side, until I was ready to start brazing.

Secondly I looked at the crack between the spark plug and the

exhaust valve seat. I gave a lot of thought as to how to address

this. The important consideration was that a new exhaust valve

seat had been fitted at some time in the past, and therefore the

crack in the cylinder head only extended as far as the new seat.

This was important, because as far as I can tell, the most serious

issue around such a crack would be that a crack on the valve seat

would likely cause a hot spot and maybe burn out the valve.

As it was, after serious thought I have decided not to do anything

about this fault at the moment, I will suck it and see. If I do

need to do something I will grind out a channel (probably about

a centimetre in depth) along the length of the crack (about 7mm)

and have it cast iron welded - but this would mean having to remove

the valve seat as well and then fit a new one afterwards, quite

a radical operation, and maybe unnecessary.

Incidentally, when questioning what causes cracks like this, I

am not entirely sure - as it is not uncommon, but I suspect that

it is because the valve seat was fitted with an interference fit

that was too extreme and it overstressed the iron. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This

photo shows head just after being

brazed. New fins have been added and

exhaust port\heady steady rebuilt

This

photo shows head just after being

brazed. New fins have been added and

exhaust port\heady steady rebuilt

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Exhaust Port Repair

The most difficult job was how to restore the exhaust port. It

looked like at some point in its life someone had dropped the

head and it had landed on one of the head steady posts, the one

that sits directly over the exhaust thread, and had completely

broken it away. It had been such a serious crack that even a section

of the exhaust port itself was missing, complete with thread.

However, the good news was that the crack ended just where the

threaded area finished, and it did not extend into the port itself,

therefore, providing a good exhaust washer was used to give a

full seal, then in reality the broken section could 'almost' be

considered cosmetic, as there was still a lot of good thread in

place to allow the exhaust nut to screw in. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

That did not change anything though,

I still wanted to effect a repair that would restore the exhaust

port to its original state, and once painted would look effectively

the same as the original.

To achieve this I had first to re-manufacture the missing piece

(or pieces as it turned) of the head steady and exhaust port.

Eventually this turned out to be 4 components - the upright threaded

'steady' component, manufactured from round bar on the lathe,

then drilled and tapped with the correct thread. 2 small vertical

fins that come off the steady, made from plate, and finally a

thicker piece of plate which when filed to shape could be wedged

into the broken exhaust port and act as a platform to mount all

the other 3 parts on, and then build around with brazing filler.

Once I had fabricated the parts, the next job was to braze them

to the head. Brazing is perfect for ths kind of job, due to its

excellent gap filling qualities, but there are a few tricks to

ensuring you get get good results and nice flowing fillets when

brazing cast iron. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As

can be seen, at this point the braze

has completely covered the plate

of steel that had been placed inbetween

the broken port, and has been directed

to fill the remaining gaps

As

can be seen, at this point the braze

has completely covered the plate

of steel that had been placed inbetween

the broken port, and has been directed

to fill the remaining gaps

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Brazing Cast Iron

First off, it goes without saying that all parts to brazed must

be spotlessly clean and have any oxide or dirt removed. To achieve

this with cast iron I will normally use a rotary wire brush -

but blasting is better.

Probably the most important factor when you are dealing with cast

iron (either brazing or welding) is the use of pre and post heat.

This is absolutely vital to ensure that you have enough heat in

the head so that the braze will melt, instead of the head just

absorbing the heat given off the torch. It will also ensure that

the head does not crack, which is always a risk with cast iron

if it is heated up or allowed to cool too quickly - for this reason

the head needs to be post heated and allowed to cool down slowly

after the brazing is complete. The kitchen oven is perfect for

this task (I am sure your wife wont mind, mine is used to it .

. . ), you need to keep it in until the head is 'spit hot', i.e.

you can spit on the head and you see the spit immediately bounce

off.

Obviously, you need to use proper brazing flux for this job, I

normally mix a small amount with water, which I brush on to the

areas to be brazed, to protect them from oxidisation and aid flow,

but I also dip the brazing rod into the powder. If I remember

correctly (from my college welding days) it is also a good idea

not to use a strong oxidising flame with cast iron as this increases

the chances of cracking, instead a neutral or slightly acetylend

flame is best.

Finally, when you commence the braze, it is very important to

put the flame to the area to be brazed and let the brazing rod

flow to the heat. It can be very disconcerting when brazing cast

iron, because of the amount of heat the head absorbs, and a common

fault is to place the rod into the flame in vain effort to melt

the braze, where it just 'globulises' (not sure if that is a real

word, but I like it), but does not adhere to the base metal. If

you get it right, the braze should just flow onto the area to

be brazed and you can get it to follow the torch, nicely flowing

across the base metal as it goes, and building up a pool on the

surface (or fillet if desired) as you progress. It is important

to remember that brazing does not provide 'penetration' with the

base metal, unlike welding, therefore there must be a certain

amount of 'pool' over the two pieces of metal to be joined, to

ensure strength in the join afterwards. This is important to remember

when grinding down the braze of any fins you have had to repair.

By the way, it goes without saying that one of the most difficult

facets of cast iron (welding) is that it tends to 'collapse' when

it gets molten - if that starts to happen when you are brazing

it, then you are using too much heat! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Looking

down on the re-fabricated head

steady from above, you can see

the two small fins that were welded

to the threaded upright, before

the whole unit was brazed in place.

I then ensured braze flowed around

the full area, to fill any gaps

between the fins. Small beads

to the right of braze are the

remnants of the flux

Looking

down on the re-fabricated head

steady from above, you can see

the two small fins that were welded

to the threaded upright, before

the whole unit was brazed in place.

I then ensured braze flowed around

the full area, to fill any gaps

between the fins. Small beads

to the right of braze are the

remnants of the flux

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Completed

head with the newly fabricated

head steady on the left. On

the right is my other spare

Inter head, as comparison

Completed

head with the newly fabricated

head steady on the left. On

the right is my other spare

Inter head, as comparison

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Finished

head after a first coat of

paint. I am pleased to say

it is pretty much indistinguishable

from the other head

Finished

head after a first coat of

paint. I am pleased to say

it is pretty much indistinguishable

from the other head

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anyway, so much for the theory . .

.

As it happens, in this case the job went reasonably well. Having

first got the head suitably spit hot, I was then able to braze

in the small wedge of steel into the exhaust port. Once I had

got this far I was able to rest the upright head steady post on

it (I had already welded the two small upright fins to the post)

, and then braze the entire post to the base. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Once I had all the pieces in place,

I then very carefully built up the braze pools, first on top of

the exhaust port, then turning the head over and working from

the thread side, until I was happy that any indents had been filled

and the shape was basically flush with the original contours.

Normally when brazing I would not be too fussed about building

up the braze more than needed, then reshaping with grinder and

file afterwards. However, with this job I was aware of how difficult

and fiddly it would be too grind down the braze aftewards, so

I was more particular to ensure that I kept braze to a minimum

and only filled the area as economically as was needed. In this

case, luckily things went well and I was soon able to return the

head to the oven to let it cool slowly.

With the brazing of the head steady completed, and looking pretty

reasonable, the remaining jobs - i.e. fitting new valve guides,

cutting the seats and fitting valves will wait until a new batch

of valve guides I am having made are ready, which as I write this

in mid May, should not be more than a few weeks. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

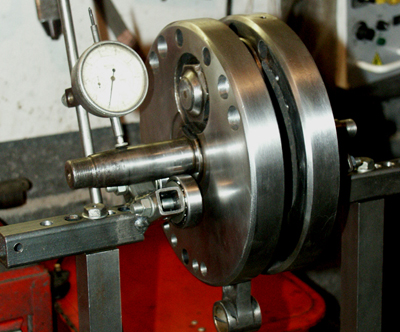

Balancing Crank |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Crank balancing tool,

ideal for the job

Crank balancing tool,

ideal for the job

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As I mentioned earlier in the article,

I had previously checked the crank for trueness, it running within

2 thou (thousandths of an inch) across its full length. The Bigend

bearing also felt pretty good, so I decided to leave well alone

for the moment – there is no point wasting a perfectly serviceable

original Bigend, we will see if it stays good, given the state

of the main bearing – although I expect it will last at

least a couple of thousand miles, (about 10 years use at my current

burn rate).

To measure run out on crankshafts, I had made my own crank balancing

frame some time before, and very useful it is too (after many

years of using some large steel pillars I have, with vee blocks

on top). This frame is fabricated from some very substantial solid

1” square bar I found in my dad’s workshop (thanks

dad – I heard you swearing as I ‘borrowed’ it),

and I then fitted a round bar assembly, with adjusters for holding

a dial gauge. Rather than vee blocks I then made a fabricated

assembly for holding 4 ball bearing assemblies, in vee formation,

that the crank could sit on. One of these sits slightly higher

than the other, as Norton mainshafts are of different diameter.

The whole top assembly is adjustable for width, as is the main

frame, for dealing with different cranks. It does not take up

much room, and is just bolted into the vice when needed. It is

well worth making one if you are intending to assemble cranks,

or change balance factors (necessary whenever you change piston’s

with differing weights).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Calculating Balance Factor

Balance factor for SOHC Norton 500 engines should be approx 66%-68%,

erring towards the 68% (although I suppose this depends what revs

you intend to run the bike at). Some time ago I was fortunate

enough to buy a couple of lovely original Hepolite International

(petrol) pistons off that old Norton stalwart, Julian Harvey (Hi

Julian if you are reading). One of these pistons would be perfect

for this engine, so I measured its weight (with gudgeon pin and

circlips), weighed an International conrod, and estimated the

top third of its mass (this is considered the reciprocating element

of a conrod) and added up the sum of these elements. I then calculated

what 67% of that mass would be. I then subtracted the top third

weight of the conrod from this final amount (don’t forget

that when balancing the conrod weight is already attached to the

crankshaft!), and that gave me the final weight I needed to hang

from the crankshaft to give a ‘neutral’ balance when

balancing – i.e. the crankshaft should not stop in any one

spot.

I have a collection of small brass weights I use for this, and

a plastic screw top peanut container, with a wire hook which is

perfect for hanging on the end of the crankshaft. Initially I

hung this from the crankshaft and then placed weights in it until

the crankshaft was neutral. I then placed the container on an

accurate set of scales, and took a reading, which told me it was

50 grams out from the desired rate – hey presto. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stage 1: Having cleaned

up the crank, I measured it for trueness, on my crank balancing

setup - it was within 1.5 thou" along its full length

- which is good

Stage 1: Having cleaned

up the crank, I measured it for trueness, on my crank balancing

setup - it was within 1.5 thou" along its full length

- which is good

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stage 2: To get balance

factor to 67% using Hepolite Inter piston, I needed to

add 50 gram to bobweight side. I tapped holes (12mm) to

take plugs on both flywheels

Stage 2: To get balance

factor to 67% using Hepolite Inter piston, I needed to

add 50 gram to bobweight side. I tapped holes (12mm) to

take plugs on both flywheels

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In this case it was the bobweight

side (opposite Bigend) that was light, which did not surprise

me, because it looked like this side had had additional lightening

holes added at some time in the past. I ‘ummed and ‘aahed

for some time on the best way to get round this, but thought in

the end the most expedient method would be to drill and tap those

holes, so I could add Hex head (i.e. Allen spanner) grub screws

of varying lengths. Doing this has the advantage that if I change

pistons at some time in the future, adjusting balance factor should

simply be a case of changing grub screws.

I decided on a 12mm metric thread, as hex head grub screws in

this size are easy to get, and come in a variety of lengths. I

bought a 3 piece tap set (course thread) and then it was just

a case of carefully tapping each hole – first with the taper

tap to ensure the thread started easily, then finally the plug.

This is a big thread, so if you try it yourself make sure the

flywheels are held firmly in a vice (in the photograph you will

see a large screwdriver inserted on the opposite side to stop

the flywheel spinning) and use plenty of fluid.

I then measured out 4 plugs that approximately equalled the missing

weight and screwed them in, two on each flywheel, one on either

side of the mainshaft\Bigend centre line. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stage 3: Having previously

worked out the number of inserts neeeded to get to the

required weight - I then screwed these hex plugs into

the flywheeels with Loctite

Stage 3: Having previously

worked out the number of inserts neeeded to get to the

required weight - I then screwed these hex plugs into

the flywheeels with Loctite

|

|

|

|

Stage 4: Final task

was to centre punch the inserts - I had previously put

a nick in the head of each one, for this purpose

Stage 4: Final task

was to centre punch the inserts - I had previously put

a nick in the head of each one, for this purpose

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stage 5: As can be

seen, with the correct weights hanging from the conrod

(in plastic container), the Bigend eye sits almost

midway - which equates to 67% balance factor

Stage 5: As can be

seen, with the correct weights hanging from the conrod

(in plastic container), the Bigend eye sits almost

midway - which equates to 67% balance factor

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Before finally screwing the grub screws

in, I just attached them temporarily, so I could check the balance

factor once again (don’t forget the tapping operation will

move a little bit of weight), this was now pretty much spot on

– good stuff!

I used Studlock fluid on the grub screws to stop them shifting,

but for added security I also ground a couple of nicks in the

head of each one, which I centre punched once they were tightened

into the flywheels for additional security. I was quite pleased

with this in the end, and hope this will provide a relatively

smooth engine in use – as always, we will see. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|